WASHINGTON — After decades of preliminary evidence, modest claims, and at least two viral TED Talks, scientists on Monday confirmed what doctors, trainers, and parents have been insisting for years: exercise works.

The peer-reviewed study, published in the Consolidated Review of Preventive Health, distilled data from 3,149 randomized controlled trials and concluded that regular physical activity reduces the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and premature mortality by statistically significant margins while improving mood, sleep quality, and cognitive function.

"The evidence is robust and consistent across age groups, socioeconomic statuses, and baseline fitness levels," said lead author Dr. Marianne Cho, a professor of kinesiology. "We observed a 24.7 percent reduction in all-cause mortality for participants who engaged in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week."

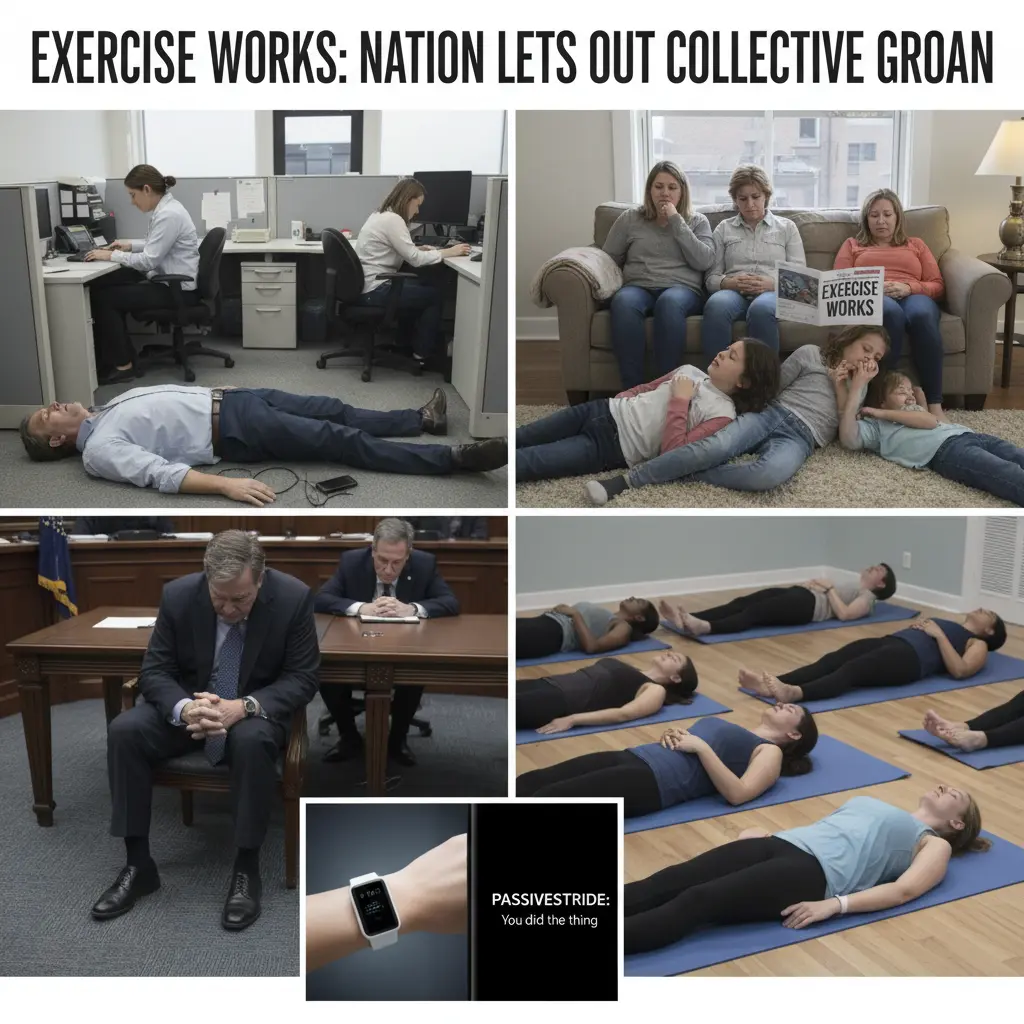

The announcement prompted a swift, unified response across the nation: a long, low groan that began in living rooms and spread to office cubicles, yoga studios, and several congressional hearings. Within minutes of the press release, social media timelines filled with photos of people lying on their backs, staring at ceilings while emitting audible exhalations.

"This is exactly the thing I didn't need to hear today," said Greg Fletcher, 42, from Des Moines, who described his reaction as "a groan with a little sigh of existential resignation." Fletcher added that he had dutifully read the first paragraph of the study before resuming his planned 37-minute nap.

Public health officials said the findings, while unsurprising to experts, present a logistical challenge: motivating a population that, according to a separate nationwide poll, prefers reorganizing their spice rack (21 percent) or knocking the dust out of recyclable grocery bags (17 percent) to going for a brisk walk.

"We are not surprised by the results," CDC Director Halima Reed said in a statement. "We are mildly disappointed on behalf of the country."

Fitness and tech companies swiftly adjusted their marketing strategies. InstantFit, maker of the StepSerene app, announced a new product called PassiveStride — a wearable that simulates the biometric readings of a walk while the user remains seated.

"For those committed to the appearance of health," said CEO Mark Donnelly, "PassiveStride provides heart-rate mimicry, calorie-estimate mirroring, and a soothing narration of 'you did the thing' by a voice actor."

Insurance companies, meanwhile, began discussing incentive programs that would reward policyholders for minimal movement. "We are exploring the use of calibrated groan-detectors to verify effort without requiring actual exertion," said a spokesperson for United Mutual, noting that preliminary models can differentiate a groan of protest from a groan of sincere exertion.

Local governments reported practical adaptations. The city of Portland announced a pilot "Walking Hour" in which traffic lights would be extended to allow people to walk slowly between coffee shops, while a church in Iowa scheduled a weekly "Forgiveness of Gym Memberships" service for parishioners too burdened by the study's conclusions to attend actual workouts.

Not everyone was resigned. "This study gives us an opportunity," said Dr. Eliza Navarro, a behavioral scientist who studies habit formation. "Small, manageable changes—like 10-minute walks after meals—have measurable benefits."

Her optimism was met with a collective, sympathetic groan from a nearby office where a meeting had just been rescheduled to discuss options for making groaning more ergonomic.

By late afternoon, consumer search trends showed spikes for "exercise hacks," "exercise substitutes," and "how to sound exhausted without moving." National spokespeople advised citizens to take whatever action felt best for them, then lie down and think about maybe trying it tomorrow.